A Scala Love Story: The Annotated Prologue

I coded in Python for a long time and it was my first love. To be honest with you though? Scala just hits different. I’m definitely riding the high of a new toy and it’ll take some time to return to the equilibrium of “pick the right tool for the job”. For now, I’m just excited to get to know Scala because it’s going to open up doors to tackle fun and challenging problems. We’ll begin with the first challenge of any programming relationship: how to install Scala on your machine.

This blog post is unlike most posts I have written. I’m essentially writing a tutorial for the first time. It will be rough around the edges. My primary goal is to piece together information that you would be able to find on different pages across the internet. For example, Scala’s download page says: “go download Java”, but leaves it to the reader to decide how to do that.

Great tutorials or Getting Started guides often assume knowledge of the reader. Make no mistake, knowing your audience and making the intentional tradeoff to not spell out every detail is effective writing. However, I also believe that it can create a barrier where one need not exist. A little scaffolding can go a long way which is why I’ve been playing with this idea of Annotated instructional web pages (a riff on Annotations in Java). Think of it as Genius.com (and in fact, Genius provides an API to handle such creative annotation cases). I try to augment great content by removing barriers and anticipating asynchronous discourse (e.g. “How do I download Java?”).

This post is my first attempt at annotating documentation. Going back to tradeoffs, I’m taking an opinionated stance on some things that the original documentation left to the reader to decide. The content herein is not comprehensive. It does aim to provide sufficient information in a single place for someone to properly download a working version of Scala on their macOS.

How To Install Scala

Install Homebrew

Many of the following steps depend on a package manager called homebrew. To install, run this command in Terminal:

/bin/bash -c "$(curl -fsSL https://raw.githubusercontent.com/Homebrew/install/master/install.sh)"Package management is almost always a pain. Having previously avoided homebrew (it’s probably more accurate to say I only used Python so conda and pip were enough for me) and been re-introduced, I think it’s worth it to stick to homebrew when possible. It probably won’t always be the right tool but I think standardizing one’s toolkit is a worthy investment.

Install Java

According to the Scala website, the recommendation is to download Java 8 or Java 11. I downloaded using homebrew.

brew upgrade

brew tap homebrew/cask

brew tap homebrew/cask-versions

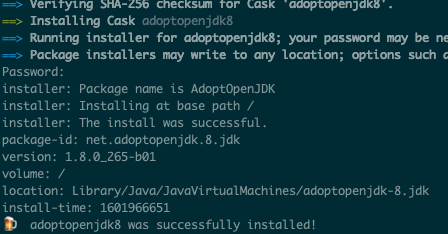

brew cask install adoptopenjdk/openjdk/adoptopenjdk8

The installation output should note where Java 8 is now installed (i.e. which directory path). Note here the line about base path and location.

Install jenv

I also recommend installing jenv. Similar to homebrew, it helps manage the various Java versions you are using when working from a command-line interface (CLI). You can install it using homebrew: brew install jenv.

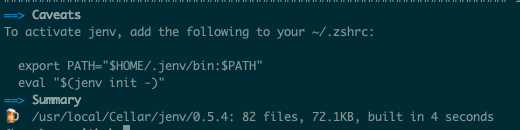

After a successful installation, you will need to add the provided code snippet under Caveats to the startup script of your Terminal. The output of the successful installation also gives a hint as to which file you will need to modify. In this example, it’s the ~/.zshrc file.

If you are familiar with vim or other text editors, feel free to use them to edit the file. Since escaping vim (and doing anything at all on vim) can often be a jarring experience, I recommend using Sublime Text. As luck would have it, it can also be installed via homebrew: brew cask install sublime-text!

You can then use the command subl ~/.zshrc. This will open a new Sublime window and allow you to paste the code snippet under Caveats. Your terminal may suggest using another file, and you can replace ~/.zshrc accordingly. Additionally, it’s worth noting that Sublime is free, but will occasionally prompt you to pay up – you can safely ignore if you don’t have the means.

To finalize jenv installation, run the command jenv enable-plugin export in the Terminal. This allows jenv to set JAVA_HOME environment variable which turns out to be pretty important to getting the Scala shell interpreter to work as intended, especially if you have multiple versions of Java in your system.

With jenv installed, you’ll want to add the version of Java that you have just installed. Remember the base path and location we saw earlier? Concatenate base path and location and in that directory, find the bin directory. In my example, it ended up being in the subdirectories /Contents/Home. Use them in the command jenv add {base path + location + /Contents/Home} to add your Java version to jenv. To see the names of all available versions, run jenv versions. Now in the Terminal, you can set a global/local Java version using jenv global/local {version_name}. Local in this instance refers to the current working directory.

Install Scala and sbt

Wow. We made it. Let’s skip the pleasantries:

brew install scala

brew install sbt

As per the documentation from Scala, Scala versionining works on a per project basis. This is worth mentioning because I know I will be using IntelliJ to write the code so it’s important to know how to manipulate Scala versions on the IDE. I’ll explore more ways to manage this later on, but for now, I want to call out one of the outputs from the Scala installation:

To use with IntelliJ, set the Scala home to:

/usr/local/opt/scala/idea.

At this point in my own learning, I don’t know a lot about sbt other than it’s going to help us build and compile our code during development (it’s a Scala Build Tool). One of the things I’m super excited about is being able to recompile when files have been changed.

To confirm your installations, you should now be able to run these commands without issue:

scala --version

sbt --version

If the Java version was set up as intended with jenv, typing in just scala should return output of which version of Java it’s using. If the two match, jenv and your Java version management was a success. You can exit using :quit.

The sbt command will take a while to run the first time around and will also likely download a bunch of things. This one also has a really nice Caveats section that won’t be immediately helpful, but reading it feels like it’s already going to save me big headaches down the line:

You can use $SBT_OPTS to pass additional JVM options to sbt.

Project specific options should be placed in .sbtopts in the root of your project.

Global settings should be placed in /usr/local/etc/sbtopts

Here are some of my sources:

- Java Installation

- jenv GitHub

- And many other Google searches.

Conclusion

Writing annotated work was an extremely difficult experience. This post took me a month to get through because there was always something more I wanted to add. I think this experience served to highlight the difficult work of writing documentation. It also validated the omission of information by more experienced writers. That said, I still think there’s a space for deeply annotated work and I hope the work presented here will be of value to someone. The more we take the best of tools like StackOverflow and SparkNotes, the more inclusive we can be of newcomers. I’m excited to keep exploring annotations, and its cousin associative learning, to better the engagement experience with learning material.